You may have heard that a spacecraft just passed by Mercury—or not. The current spate of billionaires and actors going into space has kind sponged up all the bandwidth for space-related news stories of late, so you may have missed it.

Here at the Planetary Broadcast Network, however, we believe that this BepiColombo flyby of the innermost planet of our solar system is more important than any number of entrepreneurs and fictional space captains adding “flew past the Kármán line” to their resumes.

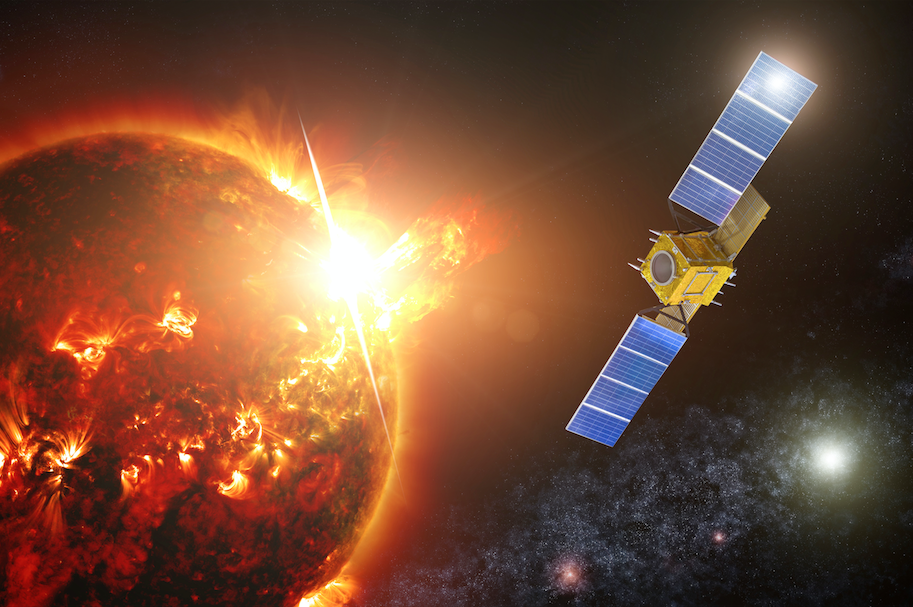

The BepiColombo Mission is a joint project of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA). It consists of three spacecraft—a propulsion unit and two orbiters—that launched together on October 20th, 2018. The stacked units travel using solar electric ion thrusters (which sounds awesome enough to be featured in a future article) and gravitational slingshots from both Earth and Venus to reach Mercury, which is around 61.5 million miles away.

The images captured on October 1st, 2021, are from the first of six planed fly-bys of Mercury, taken at a distance of 1502 miles from the surface. The date is fitting, as it would have been the 101st birthday of the mathematician and engineer Giuseppe Columbo, for whom the craft is named. The remaining fly-bys will take place over the next 4 years, until the mission reaches a close orbit around Mercury on December 5th, of 2025. Once there, the two orbiters will split off and work together to gather data for up to two years. Researchers hope that they will shed light on mysteries discovered by the two previous missions to Mercury. Perhaps the most intriguing of these is the water ice that lies in permanently shaded polar craters, found by NASA’s Messenger spacecraft in 2012.

Reaching Mercury poses some interesting problems. First, the speed of the eccentric orbit of what ancient astronomers referred to as “the swift planet” is quite high—about 29 miles per second, or well over 100,000 miles per hour. This rapid orbit takes Mercury around the Sun every 88 days, and it’s why the Romans named it after their speedy messenger god. Once BepiColombo reaches the vicinity of Mercury, the six fly-bys will allow the planet’s gravity to pull the spacecraft into a close orbit. The intense gravity of the Sun makes these trajectory calculations tricky, to say the least.

Another issue is temperature; Mercury has the largest daily temperature variation of any planet in the Solar System. Its proximity to the sun means daytime temperatures as high as 840 degrees Fahrenheit, while at night the lack of an atmosphere means that little heat is trapped on the planet, so temperatures can go as low as 275 degrees below zero. BepiColombo is a solar powered craft, but its two 14-meter-long solar arrays can’t face the sun directly; the intense heat in the vicinity of Mercury would degrade them. Instead, they have to rotate constantly to keep their temperature below 390 degrees.

Overcoming these obstacles is an accomplishment in itself, but this mission is much more than an engineering exercise. The two orbiters have different scientific instruments; the craft built by the ESA will examine the surface and internal composition of Mercury, while the JAXA vessel will study the magnetosphere of the planet. This will help researchers understand the origin and evolution of a planet close to its parent star, as well as give us the most comprehensive information on Mercury ever collected.

Additionally, the mission will also test an aspect of Einstein’s theory of General Relativity by making highly accurate measurements of the gamma and beta parameters of the calculational tool known as “parameterized post-Newtonian formalism.”

This reporter has no idea what that means, but it sounds very important, so you can count on the Planetary Broadcast Network to follow up on it, and any other breaking stories about Mercury. Stay tuned, and become the educated voter that the plutocrats fear.