Welcome to another installment in our ongoing series on physics concepts that we hear all the time and don’t actually understand.

Today’s buzzword is “Dark Matter” – and no, not the TV adaptation of the sci-fi comic book. Or the completely unrelated movie. Or the also completely unrelated novel, or the TV show being adapted from that novel.

Perhaps it’s such a buzzword because the term “dark matter” sounds so much racier than its original label, “missing mass.” It’s obviously a much more marketable handle, but scientists never seem to consider that sort of thing.

Although it may seem like a recent development, dark matter has actually been speculated about for quite some time. It was first suggested in a lecture given in 1884 by William Thomson, the 1st Baron Kelvin; that temperature scale that most of us never use is named after him. Based on observed velocities, he calculated the mass of the Milky Way Galaxy and found that it was much larger than the mass of the visible stars. From this, Lord Kelvin reasoned that the missing mass implied that many of the stars in the galaxy must be what he called “dark bodies.”

About 20 years later, the mathematician Henri Poincaré referenced Kelvin’s work, calling it matière obscure (which is “dark matter” in French). In the early 1930s, the Swiss physicist Fritz Zwicky also determined that there must be some kind of mass that is invisible to us, and he called it dunkel Materie (“dark matter” in German).

Many of these early findings were later discovered to be erroneous—Zwicky’s calculations, for example, were off by an order of magnitude—but as measurements were made with greater accuracy, the overall finding was confirmed. There are observed gravitational effects that simply can’t be explained under our current understanding of gravity, without the presence of more matter than is visible.

Most physicists believe that dark matter makes up as much as 85% of the mass of the universe. There is something that causes these anomalies in velocities and mass-to-light ratios, and that something appears to be a kind of matter that doesn’t interact with electromagnetic radiation. In other words, it doesn’t absorb, emit, or reflect light, making it very difficult to detect. It seems to only interact with normal baryonic matter by way of gravity.

OK, so it’s out there, but what is it? Since no one has yet directly observed it, there are a number of ideas; the most popular conjecture at this point is that dark matter is some sort of elementary particle that hasn’t been detected yet. This includes hypothetical particles like “axions” and “weakly interacting massive particles,” also known as “WIMPs”. Numerous experiments aimed at detecting these dark matter particles are ongoing, but thus far they’ve had no success.

Some researchers believe that dark matter doesn’t exist at all, and the reason it’s implied by the mathematics is that our current grasp of the laws of gravity is flawed. It’s possible that dark matter is simply a type of gravity that we haven’t uncovered yet, or that we don’t fully understand. By modifying the current model to better explain the observed gravitational phenomena, the need for dark matter can be eliminated. There are many such modifications being studied; Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND) is perhaps the best known of these alternative theories.

Discussing the differences between MOND and the dark matter model is beyond the scope of this article (and honestly, beyond the grasp of this reporter), but when there are new developments in the search for dark matter, you can rest assured that the PBN evening news will keep you advised of them. As ever, the Planetary Broadcast Network is your source for all the news you need to be a contributing member of our great society.

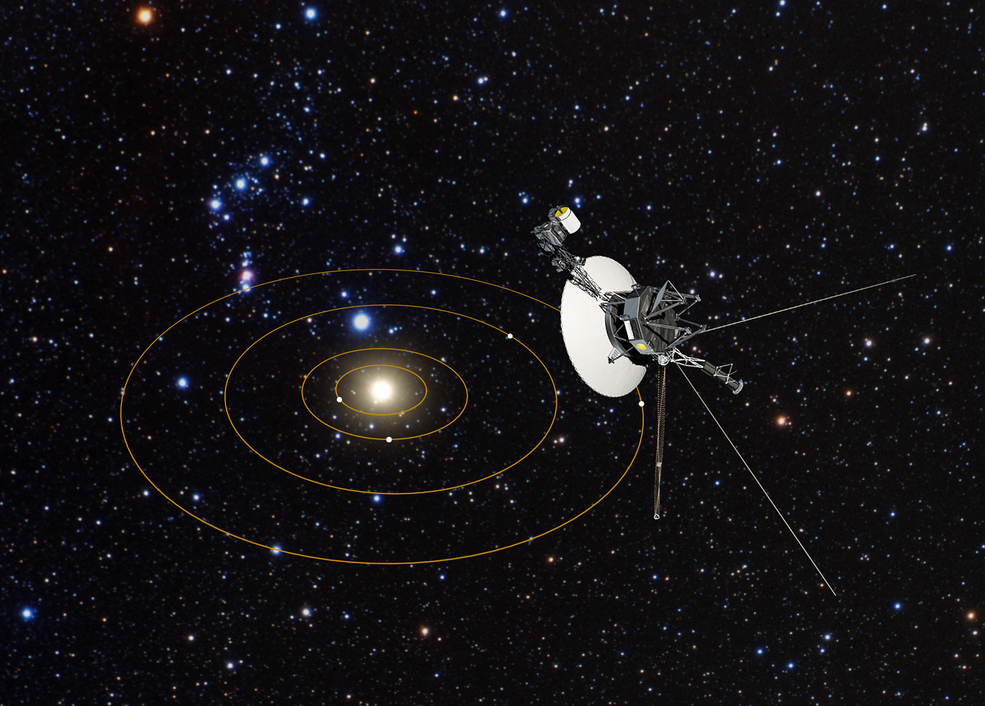

Photo Credits: nasa.gov