NASA’s Space Telescope Science Institute (STSci) lacks the rockstar name recognition of places like the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Cape Canaveral, or Kennedy Space Center, but that may be about to change. STSci is the mission operations center for the recently launched James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), and as it comes on line, its findings are expected to revolutionize the study of deep space.

Located at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, STSci is also the operations center for the Hubble Space Telescope and the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope (currently in development and slated for launch by 2027), but all eyes are currently focused on the JWST. Not surprising, given that it was twenty years in the making and sports a $10 billion budget. Many, both in government and in the scientific community, are waiting impatiently to see what all that planning and expense will get us. Unfortunately, despite recent media coverage of JWST reaching its destination, the wait is far from over.

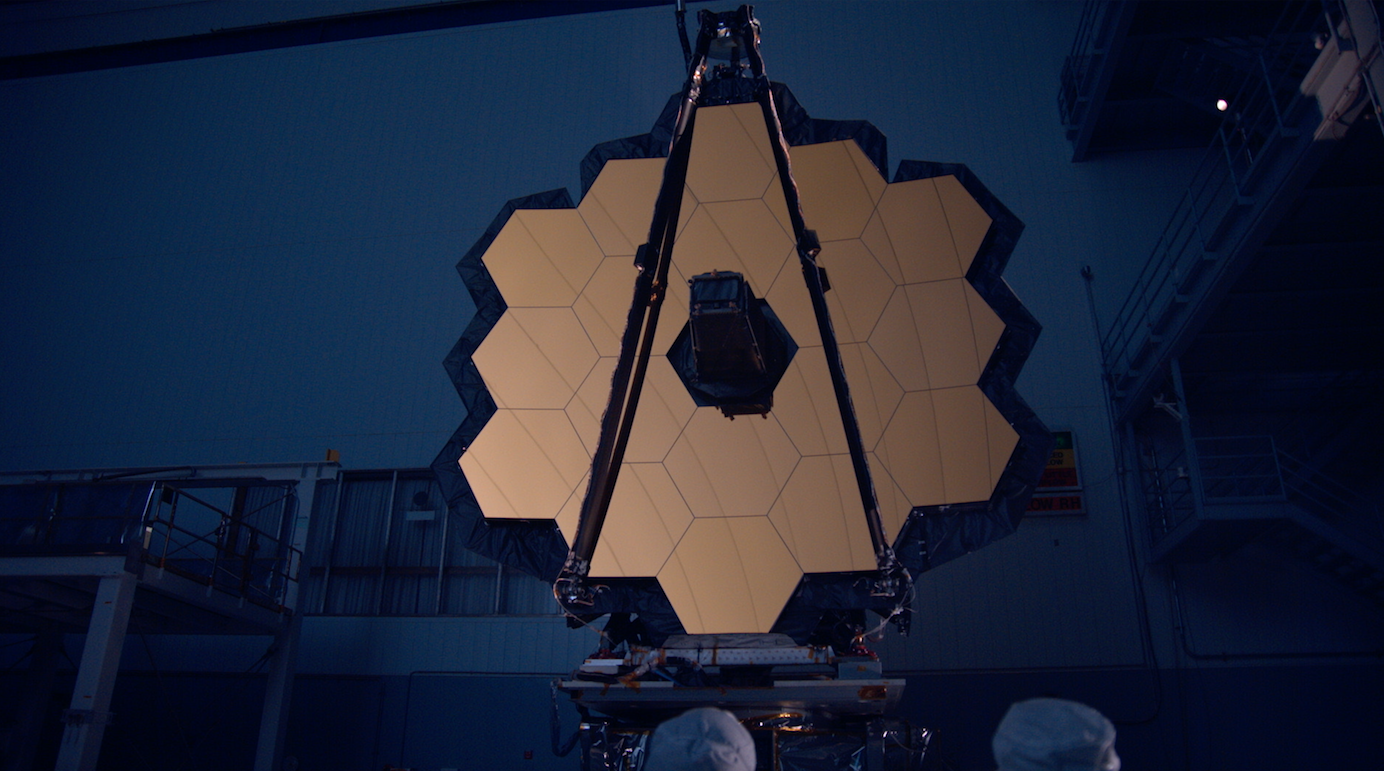

Once JWST arrived at the L2 Lagrange point, the crew at STSci began the painstaking process of deploying its sunshield and massive mirror, then calibrating its cutting-edge instrument package, while making small but crucial course corrections to align the telescope and lock it into position in space. This deployment is a more intensive job than you might think—it takes 2 weeks just to get all of the 18 hexagonal sections of gold-plated beryllium unfolded and in place to make up the 21-foot main mirror, which in 6.25 times larger than Hubble’s main reflector. Each of those sections can be moved by 6 actuators, which the technicians at STSci will use to position the array; this is also expected to take a week or two to complete. Once JWST’s external structures are fully deployed, they can begin cooling it all down with the on-board helium cooling system. This three-week process will cool the telescope down to around minus 400 degrees Fahrenheit. Extreme cold is necessary for the instrument package to be able to detect the very long wavelength infrared light that JWST is designed for. When all of this has been completed, operators can begin the fine-tuning of the mirror and instrument package—a process that may take up to another five months!

If all this goes well, then by mid-summer the JWST will finally be ready to begin its primary missions. Although this is a vast oversimplification, the main goals of the initial five-year mission are to study the history of the universe, and to examine exoplanets that may be Earth-like. Just like Hubble, it is hoped that JWST will continue to function for an additional ten to fifteen years beyond that.

JWST’s instruments are so superior to previous space telescopes that they can detect objects up to 100 times fainter than those spotted by Hubble. This means that JWST will be able to image things that are much older and more distant than any we have ever seen before, including the earliest stages of the universe and the formation of our solar system. It will also allow researchers to make detailed atmospheric analyses of potentially habitable exoplanets—an exciting prospect in the search for evidence of extraterrestrial life, as well as for those who are seeking potentially habitable planets for future manned missions.

So, when can the public expect to see meaningful results from JWST? It’s hard to say. Some pics are already being released—images captured during the process of focusing the mirror sections—but substantial findings may take much longer.

And when those findings are made public, you can count on the Planetary Broadcast Network to bring them all to you, in digestible, bite-sized info chunks… which, incidentally, reminds me of our sponsor today, Jibble. The good people at Jibble believe in supporting the PBN Evening News so every citizen can be an informed participant in our great democratic experiment. Stay tuned for more stories like this one, and don’t forget to try Jibble’s new JWST-inspired flavor, ‘Infrared Beans and Rice’—you’ll find it everywhere fine foods and food-like substances are sold.

(Photo Credits : nasa.gov)